Selected Writing

Fiction

RIDING THE STORM

James Knisely

(First appeared in North Dakota Quarterly 80.1 Winter 2015 [Nov. 2014])

I.

Kerouac missed his chance. Jack, I mean, not the other one. He missed his shot at immortality. Sure, he’s famous, but he had a chance to become and to soar and finally to tell us things we didn’t already know—and he blew it.

He went to the mountain looking for God but came face to face with only himself—and The Void. Well, after all, he was a fire lookout. Any lookout who has ever looked out from some lonely mountain has met The Void. But at the end of his only summer on the mountain, Kerouac ran away. And what he lost by never coming back was the chance to discover that the void is not merely the “abysmal nothingness” he found (mainly within) or the empty silence of the mountain Hozomeen, and to see for himself that the void is also the chaos, the creation of galaxies by the flap of a wing. What he missed was the chance to discover that the void and the chaos are one, and together are the face of God.

He abandoned the mountain for a couple of reasons. One was his disappointment, his feeling that Desolation, “that hated rock-top trap,” had let him down. The other was the girls of Mexico City. Let’s not blame our loss on them—they were only busy being who they were. But maybe if he hadn’t craved their company so much. . . . All he had to do was return to his mountain for another summer or two, as Snyder did, or Whalen, and he might have seen everything for himself. But the señoritas called and Jack went, never to see the mountaintop again.

II.

In June, 1961, just a few years after Kerouac’s legendary sojourn on Desolation Peak, I arrived for the summer at Little Mountain Lookout, a lonely sentinel above Washington’s Cedar River.

This was my second summer on the Cedar. I was still searching for my voice as a novelist or a poet, so in the summer of 1961 I came back to the solitude of the mountain.

Kerouac’s lookout was a sturdy cottage on a barren summit in the North Cascades. Mine was a very tall tower atop a rather small mountain a hundred miles south of Desolation. At 110 feet, the Little Mountain tower was said to be the tallest in Washington State, 20 feet higher than the fabled structure on Tiger Mountain to the west. And not just tall but spindly, a tinkertower of ancient sticks so skinny and wobbly it put me more in mind of eternity than Kerouac’s cozy bungalow (I’ve been there) ever could.

The tower had no room for lodgings of any kind. The tiny cabin or “cab” at the top had space only for an Osborne Fire Finder with a two-way radio tucked underneath and a glass-footed wooden chair. The catwalk around the outside of the cab was just wide enough for me to survey my domain, as I was required to do four or five times an hour.

I lived in a slightly larger cabin in the clearing below the tower. Food and water came up the mountain by truck. Electricity was produced by a gas-powered generator near the base of the tower. The generator charged only a battery, and the battery ran only the radio. Since the living quarters and the cab were separated by 110 vertical feet of wooden steps, the tower gave me a modicum of exercise to compensate for a job that mainly required sitting around—hopefully getting in a little reading or writing—and shuffling about for ten or twelve watchful hours a day.

The lookout towered above the already old second-growth Douglas firs and hemlocks that covered much of the mountain, making it a prime target for lightning strikes, from which it was protected by a grid of heavy copper wires. A wire with a sharpened point rose from each corner of the cab to just above the peak of the roof. These four lightning rods were connected by a wire that ran around the top of the cab and by another wire around the bottom. Each of the four lightning rods continued down its corner of the cab and down that leg of the tower to metal posts buried in the ground, creating a grounded “cage” that surrounded the cab. In theory, the cage protected the interior of the cab . . . and anyone foolish enough to be in it during a storm. That’s what they said.

#

My job in the summer of 1961 was to stay at Little Mountain during dry weather, which even in the Cascades could last as much as a month at a time. I worked for the Seattle Water Department, guardian of the river from which the city drew its water. I ran up the tower first thing each morning to look around for smoke, then back down to fix breakfast, then back up by 8:00 to start the day’s watch. I kept watch, checking in with the Water Department from time to time, until 5:00 or 6:00 p.m., then descended to the cabin to fix dinner. After running back up a couple of times during the evening, I would turn in about 10:00.

#

I was snoozing soundly one night when a hammering at the door blasted me awake. The hour was about 12:30. I staggered out of bed and found Joe Monahan on the steps—my boss. His rig idled behind him.

“Haven’t you heard the thunder?” he asked. “There’s a storm coming in. I need you up the tower.” He was heading into the upper watershed towards Yakima Pass, but he needed me to watch for strikes from here. “Stay in the cab till it blows over,” he said. “Turn your radio on, but don’t use it till the lightning has stopped. And for God’s sake, stay inside the cage.” Then he was gone.

I dressed quickly and hustled up the 197 steps of the tower to the “safety” of the cab and its cage. I turned the radio on and squared my chair around so it was touching nothing but the floor with only its glass feet.

Through the night a heavy blackness advanced from the west. At first there were only occasional flashes in the oncoming gloom, but by the time the storm reached my puny mountain it was popping in earnest. I didn’t see any strikes, but soon I was engulfed in the clouds and couldn’t see anything at all. Bursts of lightning surrounded me now in the dark and the fog, followed more and more closely by thunderclaps that rattled my trembly tower.

The cab had drop shutters that were hinged at the tops of the walls so that when they were down they covered the windows. Opened and propped up on poles, they created great wing-like eaves that covered the catwalk and protected the cab from the sun. Wing-like. I found no comfort in the thought.

As I sat in my hopeless chair staring into the fog and the murk and those terrible flashes, the hinges and bolts and nailheads of the shutters began to glow with an eerie blue light. I watched in disbelief while ghostly fireballs, tiny wills-o’-the-wisp, glimmered forth and commenced to dance fantastically on my shutters in the night.

I remembered hearing once of such a thing, a wonder called Saint Elmo’s fire. They tell me it’s an electrical discharge that occurs when a current passes through ionized air, but at the time I knew only that it had a name. I wouldn’t have doubted for a second I was getting some ionized air.

I thought very hard, though, about eternity, and prayed that St. Elmo hadn’t been part of some cruel joke. I didn’t know this either, but Carl Jung had written that St. Elmo’s fire is evidence of the existence of God. Just then it was evidence to me only of the fear of God, which began to well up in me like an icy spring.

The fireballs danced for maybe a minute, a frenzied fandango that taunted my mortality and sang to me of the chaos in which we hang suspended. Then, with a flash and a deafening clap, the cloud that had become my universe blew its charge.

The dancing lights went out. Even so, I remained frozen to my chair, carefully keeping my feet off the floor, wondering what might come next. The wind had risen in gusts that buffeted the cab and its wings like a box kite in a hurricane. I closed my eyes and prayed once more that this old tower might have one more proper shaking left in its bones.

Before long the fireballs flickered back to life. This time, as the hardware began to glow, I became aware of a buzzing behind me in the corner of the cab, the death throes, I thought, of a fly, beating its wings in a frantic struggle to survive the storm. Maybe the fly had become ionized too—or was gaping into the void. It occurred to me that it might even be involved in the destruction of a galaxy—possibly this one.

The buzzing grew louder and louder until I realized that it might not be some hapless insect after all but a terrible new sign of the wrath of the Cosmos. As the tower shook and the buzzing swelled and Elmo’s ghosties grew brighter and brighter, another flash and thunderous crack exploded just outside, and the bedlam in the corner, like the fireballs, stopped cold.

It came to me then: the buzzing mere inches from my right buttock was the sound of ten million volts of cumulonimboid energy racing to the ground (or, technically, from the ground) through the grid of rods and wires that tied my little cab to the earth. Only that cage and its groundwires stood between me and a dark and angry universe.

In spite of the peril into which I had been thrust, as a fire lookout I was useless. I could see nothing. Beyond Saint Elmo’s flameballs and the fog and those hair-raising fulgurations I saw no strikes, no fires, no mountains, not even the treetops below me; no evidence of any kind of the world in which I had thought I lived. I was adrift, staring wide-eyed into the heart of the universe itself. Yet suddenly, in the flash of a different kind of lightning, I knew that I was glad to be there. I was happy—not just to be alive but alive and riding the storm.

#

The tempest raged for what seemed half the night, though probably for no more than an hour. However long it lasted, it carried me to places I had never been and filled me with awe by an unexpected revelation: that the great void of the universe embraces both the silence of Kerouac’s mountaintop and the tumult of the chaos from which we have all so recently emerged and into which we will all so soon return. That night revealed to me that swirling about (and passing through) our pitiful selves are forces we might certainly fear but with which we might also dance our too-short nights away.

#

I’ll never begrudge Kerouac his Mexican girls. Ah, Mexico! There’s more than one way to dance the night away. Even so, I can’t help thinking that by never coming back he missed a vast and insane opportunity to discover a new dimension of the “vast and insane legend” of his life. To fly the chaos and stare into the void and dance with the blue lights of the universe—now there’s a meeting with God.

III.

After the storm that night came the rain. In the Cascades, raining is not storming; it’s what we call summer. All the same, it rained harder than usual for the rest of the night, lowering the fire hazard to nearly zero. Once the rain let up I kept watch under dark skies for another day or two just to make certain no ember or smoldering snag survived, then someone drove up the mountain and hauled me down to headquarters at Cedar Falls.

Days later I was still at Cedar Falls, swabbing the urinals and sweeping the shop. The woods remained damp, so I wasn’t on the mountain. One afternoon we received a report of smoke near the top of McClellan Butte, a higher peak just a mile or so north of Little Mountain. Loggers who were working in those days on the Cedar may have seen it. Or maybe it was spotted it from the air, I don’t remember. The airplane augured even then the demise of the lookout. In any event, the smoke was almost certainly the result of that storm—my storm.

Because I was available, I went up with the crew to the fire. Thinking I was in good shape because of my summer of tower climbing, Joe had me carry one of our 5 gallon backpack pumps, our only water supply. I wasn’t in the condition he had hoped but I managed to reach the fire, which was smoldering in a couple hundred square yards of the steep forest floor.

We spent the afternoon turning duff with our shovels and mixing it with mineral earth and wetting the hot spots as well as we could. The next day I was hauled back to Little Mountain to keep an eye on it. But we had done a good job, and the fire never flared again. Maybe I had earned my keep after all—not by the romantic heroism of flying the storm but by the gritty, sweaty work of turning the earth.

Yet that single night’s hour of wildness ignited something new in me, something astonishing, a sense of how the energy of the universe passes through us as we pass through it.

#

That was fifty years and a couple of lifetimes ago. I suppose that means I’m older now—and hopefully a little wiser. Whatever Kerouac found, whatever he learned about passing through the void, I can tell you this: he missed his shot. He could have been immortal. I’m certainly not—but I’m not Jack Kerouac. What if he had gone back? What if he had peered into the storm and passed through the chaos and lived to write about that? One day, one night, as the storm descended on Desolation, Jack might have found what he sought. And who knows what he might have told us then?

WANDERING THE MOON

James Knisely

(First appeared in ARCADE: Architecture / Design in the Northwest Vol. 24.4 Summer 2006 — Currently found at HistoryLink.org, the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History)

Some nights the wolves are silent and the Moon howls.

Dylan Thomas drank there. So did Ginsberg and Mark Tobey and Kenneth Callaghan. Tom Robbins. Theodore Roethke and Richard Hugo. No Dick Hugo am I, though; a poor wanderer I am and nothing more.

The Blue Moon is a dive. And not just murky, sticky and dense: it’s ugly. Ugly to the studs. It’s beautiful.

The bar, the booths, the ceiling are all of some snuff-dark substance reminiscent of wood. Layers of ancient varnish seem to hold the place up. Photos and posters and clippings hang everywhere, some very old, and Gus Hellthaler’s hockey helmet dangles over the bar. The bar is not so much a horseshoe as a pen, a haven for the help from the press of a sometimes lively clientele—and a natural barrier between east and west.

Beautiful.

I wander in, as into the Bohemian Quarter, and veer instinctively to my left, to the west. To the left live the lefties: former Communists (no one at the Moon claims to be a Commie any more), new-millennium Democrats, latter-day anarchists, and many who no longer give a damn. The booths and tables along the west wall were old when they were installed long ago. Books and encyclopediae festoon the shelf above the booths and are oft used, misused, borrowed, stolen and sometimes even replaced.

An omnium gatherum of humanity inhabits the booths—a lanky electrician with a tam and a white goat-beard, a silver-haired folk-rocker with a grin that brightens the cosmos, a burly day laborer with a PhD, a post-gonzo journalist or two—from all of whom the place draws its energy. They squeeze together to share pitchers of the swill du jour and talk the idle babble of the Moon. As I wander past, a powerful bulldog of a man reaches for a dictionary to settle a noisy dispute.

Past the booths and up two steps I drift into the Blue Room—the legendary back chamber of the Moon—as if into a brave new precinct. Tonight the Blue Room is empty—but on Friday nights it becomes the scene of Jack Oram’s Sleaze Club, a melange of med-school researchers, musicians and cultural hangers-on who have met there every Friday for twenty years to drink and shout and be…well, sleazy. They used to smoke (tobacco, before the ban) and still argue their research and agree on their politics and throw peanut shells on the floor to justify jobs for two or three of their own.

But not tonight. With no one in the Blue Room, I venture down the back hall to the can. The hall is a dangerous alley, narrow and dimly lit between impinging walls; brave men have withered in passing through there. Yet nowhere is the Moon’s reputation more justified than in the men’s can. The crapper and the urinals have leaked for generations, so the floor is always soggy. But just as well. The perpetual funk serves as a reminder not to get too familiar with the men’s room floor at the Moon.

The women’s room is different, a lovely oasis for the gentler sex (I’ve seen it for myself). It’s the aberration that proves the rule.

I wander out of the can (the men’s) and into the dark side of the Moon. The east side. The back room here, at the top of the steps, is the neighborhood’s empty lot. But on weekends it doubles as the stage for live music—some of it pretty good. A honkey-tonk piano stands at the back of the stage, and against the far wall rests the original bathing-beauty-on-a-sliver-of-moon sign that once warned generations of the degeneration within. (The new sign outside features the nude and uncannily identifiable bartender Mary McIntyre—a painter in her own right—by the gifted artist and Blue Moon custodian Mike Nease.)

Down the steps I come to the parallel universe called Felony Flats. The University crowd doesn’t much hang out here, except to shoot pool. The bohemians and the artists and the self-styled intellectuals don’t sit here. The people of the night loiter on this side of the Moon—and they are welcome. They are a neighborhood, too, and everyone who behaves is welcome at the Moon.

Oddly, it’s here on the felony side where the house art is hung: a towering Nease portrait of Roethke; vibrant new work by McIntyre; other work that comes and goes as it is made and sold—and some of it damn good.

While two rough-and-ready hombres play eightball, a fifty-something man with dreadlocks talks in a booth with a gaunt-faced woman who doesn’t appear to know where she is.

Only a few of my friends are here tonight. Since the smoking ban, there are slow nights at the Moon. Dark nights. Times may change, and business may pick up, and maybe once more Gus will give happy hour prices to the Sleaze Club. We’ll see. Meanwhile we can only pray (those of us who do) that the Moon will be forever Blue.

I have a beer with Andy at the west end of the bar, then decide to go home and get some dinner. I do not wander out, though, as I wandered in; one may bound out or stagger out or be thrown out, as need be—but no one ever wanders out of the Moon.

LIMPING TOWARDS THE WILDERNESS

James Knisely

(First appeared in Rosebud, Issue 63 Fall 2017)

The rap on my foot woke me in an instant. It was the cop.

“What are you doing here?” he said.

Evanston, Wyoming, September, 1965. I had thumbed my way into town at midnight from Colorado Springs and found the police station on the advice of a saintly Christian woman in the Springs who had told me police stations sometimes took in hitchhikers for the night. “Gray-bar hotels” she had called them. I don’t know how she knew that, except that she had lived through the Great Depression. I was a 24-year-old kid at the time and hadn’t lived through much.

The hoosegow was open but empty. Not a soul in the joint. I waited 45 minutes on a wooden bench for someone to show up, then stood to stretch and consider my choices.

On a bulletin board I had found a list of rules for “overnighters.” Aha! I thought. The rules said overnighters were to sweep the jail in the morning, be fingerprinted, and be out by 7:30. That seemed fair. The three cells in back were empty, so I picked out the middle cell and crashed on the bunk.

I had been asleep about an hour when the night cop finally showed up. His badge said “Chief,” but I couldn’t tell whether he was Chief of the night cops or the whole department. My guess is he was the whole department.

The Chief had just brought in a drunken citizen for a night in the cooler, and it dawned on me then what an “overnighter” was. The Chief put the drunk into the cell just past mine, but was not happy to find me in his hostel.

He let me go back to sleep then woke me at 6:00. He didn’t fingerprint me and didn’t have me sweep the jail but warned me against violating the tranquility of his town by hitchhiking through it, for which he would have me punished with 90 days of sweeping its streets. Vagrancy, he called it, ignoring the tape that spelled out STUDENT on my suitcase.

I wanted to go north through Jackson Hole, but that would mean passing through his town. Since I was bound for Spokane, he told me to head west straight out of town and not look back. Due west of Evanston, Wyoming into the deserts of Utah.

I was on my way to Seattle, where I would surprise my parents, who thought I was in New York. From Seattle I’d make my way back to New Jersey, where I was in school. I had two suitcases—a big mistake for hitchhiking. The largest had that sign on its side. Both suitcases were a little shabby, and I was dressed for the road. I hoped advertising myself as a poor student would get me some sympathy rides and reduce the risk of being grabbed for ransom. Did I say I was a little short on experience?

The Chief tossed me out of his jailhouse before I could explain that I had to whizz. There was a gas station nearby, but it was closed, so I stepped around the corner to see if the can might be open. It wasn’t.

I slipped behind the building and irrigated the weeds, then got out my map to look over my options. The highway running west turned south in Utah toward Salt Lake City before branching north toward Ogden and the deserts of Idaho. It looked like I could make Pocatello or even Butte before it would be time to look for another jail.

Getting to Jackson Hole from Evanston meant either backtracking east to catch 189 north through Kemmerer, or taking 89 north from Evanston and snaking my way along the Utah-Wyoming border, then coming into Jackson over the mountains. I had no interest in the deserts of Utah or Idaho or even the fabled nightspots of Pocatello. I wanted very much to hitchhike through the mountains and Jackson Hole and Yellowstone. I wondered whether that jerkface could really get me 90 days.

I heard the Chief come out of his jailhouse and get into his car. Past the corner of the gas station I caught sight of the Chief Car heading west. I knew in my heart he was hoping to catch me with my thumb out on the edge of his pitiful town.

I made my decision and folded the map. I stuck the map into a suitcase, then zipped everything that needed zipping and stepped around the gas station. No one in sight. I turned east.

I walked on the left side of the road so I couldn’t be accused of hitching, and made my way the block or so to Route 89, then turned north—into town. Into the Chief’s paradise of serenity.

I lugged my suitcases through what looked to me like the heart of Evanston, Wyoming, though I don’t remember seeing a storefront or a shop or even a lawyer’s office. Just houses. Block after block of old, plain, and soon very boring little houses as my suitcases began to grow heavy and my hands began to lose strength and pain began to run up my arms into my brain. Before long I realized that I was even starting to limp.

Since one suitcase was larger than the other, it was also heavier. Every block or so the hand holding the heavy bag would give out and my lower arm would spasm and I would be forced against all my instincts to stop and set the bags down. Switching hands helped a little, but not enough. My breathing was growing labored, so I used those stops to catch my breath. Even so, I didn’t like stopping. I had to get out of that town.

I wondered about the 90 days. He couldn’t do it. I wasn’t a vagrant, goddamn it, I was a student. A divinity student. And I wasn’t hitchhiking. I stuck to the left side of the street and did my best to keep my thumbs out of sight. But in spite of the pain and the heavy breathing, Chief Jerkface’s threat kept me moving.

It must have been a mile and a half through town and took me most of an hour. At the city limit I limped several yards farther, hoping to get myself out of both the jurisdiction and the sight of the Chief. I crossed to the right side of the street, then set my bags down with the “Student” sign facing back along the road.

Shortly an old green pickup came along the road from town but didn’t stop. I hoped that meant others would be coming soon.

I wondered why I did this. I had once stood beside a highway outside Umatilla, Oregon, on a frozen, sunny day in February, nipping from a bottle of cheap loganberry wine (“logie,” we called it) and staring down the snow-glint road till I had a between-the-eyes headache that worsened with every nip as the few cars on that highway passed me by. What was the fun of that?

Yet there was romance on the highways of the West. Hitchhiking had not yet been taken up by the young of the middle class, but I had somehow stumbled into the belief that Something was Out There waiting to be Found.

I had read The Dharma Bums but not On The Road. I had long held a fascination with the Beats, though I hadn’t quite realized what wildmen Kerouac and Cassady were. I hadn’t yet heard of Kesey or the Merry Pranksters, and the hippies were still just a blip on my screen.

But Dylan I knew. Dylan’s singing reminded me less of Woodrow Guthrie’s than the dusty croaking of Woody’s sidekick Ramblin Jack, but Dylan had given voice to the growing restlessness of my own generation.

A shapeless tan car passed me, maybe a Nash.

Bob Dylan I knew—yet there was more to it than that. Dylan had called forth a spirit that had haunted me all my life, a yearning for something I couldn’t quite name. “A restless hungry feeling,” he had called it. I had recently been unfortunate in love, and the face of my lost sweetheart dogged me across the land. But the yearning was something deeper and longer than that—something even as a divinity student I had never been able to pin down.

Whatever it was, Dylan had given it a name. And he had given it poetry and music. And the music and the poetry—and that dustbowl voice—had set me on the road.

Another truck, probably belonging to some local farmer or rancher, if they had farms or ranches in that bitter land, pulled out of town and accelerated past me as if I were a rock.

I had a harmonica in my pocket but didn’t take it out. I had bought it in Colorado Springs hoping to learn how to play the blues, but so far that flattened seventh had eluded me and I was convinced I had bought the wrong kind of harp. The art of sucking funky magic on those long and winding highways would have to wait until I knew how it was done.

I worried some more about the Chief. “That goddamn jerk,” I thought. I knew when he didn’t find me west of town it might occur to him that I had disobeyed his fucking command and he’d come looking for me at this end of town. I needed that ride.

Even as a divinity student I thought in terms like “goddamn this” and “fucking that.” I had Dylan and his outrage to thank for that. I had racial unfairness and unjust war and romantic disappointment to thank for it. And that restlessness—that existential sense of alienation—that struggled with faith and hope for control of my mortal soul.

A car came out along the road from 6th Street. Seeing it wasn’t the Chief Car, I poked out my thumb. It slowed as it passed me, an aging red Fairlane, then pulled onto the shoulder.

I picked up my bags and limped to the car. A man in the passenger seat rolled down the window. “Where you headin?” he said.

“Jackson Hole,” I said. “God willing.”

The man laughed. “Ain’t that the case,” he said.

The driver killed the engine and got out, then came around and opened the trunk. He was a big, brutish-looking man dressed more or less as I was. For the road. He put my bags into the trunk and slammed the lid. “Climb in,” he said.

Someone in the back seat opened the passenger side door and I climbed in. The man in the back seat was even bigger than the driver, with thinning, reddish hair. I guessed the two were in their forties. The man in the front passenger seat was younger and a little less hulky. He had a bony face and thick glasses.

We pulled onto Highway 89. The Fairlane needed a new muffler, so we shouted over the noise.

The men were rough, coarse, and ugly. Even the smaller one in front. I had spent summers working in the woods with men like these. There is no one on earth more snaggle-toothed, coarse, and fist-ready than the men who work in the woods. Except for these guys. These men took the trophy.

But they were sober—a big deal on the road. And I owed them the next 90 days of my life.

“So you’re a student, eh?” the guy on the passenger side shouted.

I agreed, though I didn’t want to get into the subject of divinity. That almost always turned weird.

“Where at?” the guy asked.

“New Jersey,” I said.

“New Jersey! Kind of a long way from New Jersey, ain’t you?”

I explained that I was from the Coast and on my way to Spokane.

“You hitch all the way from New Jersey?”

“Not this time,” I said. They all laughed.

I think I’ve said that Highway 89 ran north along the Wyoming-Utah border. I noticed we were descending a little, probably into Utah.

“Where do you stay when you’re hitchhiking?” the guy with the glasses asked.

“Probably figures to end up at a bar every night and get picked up by some cunt,” the driver said. “What I’d do.”

Everyone laughed. “What you’d like to do,” Glasses said.

“Naw, naw,” I said, “women don’t take me home. Don’t know why.”

The men all laughed again and the guy next to me spoke up for the first time. “Well hell, kid,” he said, “just stick with us and we’ll show you how. Nothin to it once you get the hang.”

“Maybe you been a student too long,” the driver said. “Where’d you stay last night?”

“In the jail,” I said.

“The jail? Naw! In Evanston? What did you do?”

“Nothing,” I said. “Just walked in and took a cell.”

“No shit!” the driver said. “You walked in and took a cell?”

“Now there’s something I never done on purpose,” someone said.

We were coming down into a broad and barren valley, now well into Utah, I thought. The road would come back into Wyoming in time and north to Jackson Hole, a place of wildest beauty. This was a place of wildest desolation, and drier than bleached dirt.

The guy next to me spoke up again. “Remember that kid we picked up a month or so ago?”

“Oh, shit,” the driver said. Glasses let out a guffaw, then stifled it. “Oh, shit,” he said.

“Did you ever hear any more about him?” my guy said.

“Maybe we shouldn’t ought to talk about that,” the driver said.

I looked out at the landscape and began to think I didn’t like this. Maybe I should have taken the Chief up on his offer. Maybe I’d have been better off with some drunk.

We were now on the floor of a desert where it looked like nothing could live. I thought of Death Valley. I didn’t like the comparison.

“Hey, that kid was a student too, wasn’t he?” my guy said.

“Jesus, Red!”

“Yeah, maybe you’re right,” Red said.

“Holy fock, though,” Glasses said.

“I know it,” the driver said, and they all laughed. “It was funny, you gotta admit.”

“Oh, shit,” the other two said and laughed again, a dirty, creepy kind of laugh.

“So . . . ” the driver said. “You hear what Jack done to Janice?”

“What, again?” someone said. I could tell they were changing the subject. But Glasses kept turning around to grin at me as we drove into the desert. The romance of the road was starting to feel somehow thin. “How you doin, kid?” Glasses shouted, and grinned again.

They talked about Jack and Janice some more then fell silent. They all seemed to be thinking—about Jack and Janice, I hoped.

Once we were well into the desert and far from any living thing, the driver pulled onto the shoulder and stopped. He turned around and looked at me. No one was smiling now.

“Well, kid,” he said. “This is it.”

I looked out at the desert. A range of hills to the east shimmered hopelessly in the bone-bleaching sun.

“This is it?” I said. It didn’t even occur to me to make a break. I had no idea what to do.

“Yeah, kid.” He cracked his door open. “Go ahead and climb out.” Then he got out and started around the car.

I wasn’t sure I wanted to get out, but I sure as hell didn’t want to stay in the car.

I opened the door and stepped out onto the cinders of the shoulder. Just ahead of us I could see a dirt road that turned off across the blistered earth and wandered toward the hills. Glasses climbed out his door and grinned again.

“We’d love to stay and fun with you,” he said, “but we gotta get to work.”

“Work?” I said.

“Phosphate mine,” he said, “—up in them hills.” He nodded towards the shimmering east.

By now the driver was at the back of the car. He opened the trunk and pulled out my bags.

“You’re a good sport, kid,” he said. “Hope you don’t mind a little funnin.”

“Aww,” I said. “Just part of the . . . fun,” I said.

“Sorry to leave you out here, but this road gets pretty good traffic. You should do okay.”

“Yeah,” Glasses said. “Travelin student. Maybe someone will take pity.”

Red got out and we all shook hands. Then they climbed back in and turned off towards the hills.

I stayed where they left me. There was no point trying to schlep my bags across the wilderness. I turned my sign to face back along the road and waited for some of that traffic. The sun was now well up over the hills.

I thought about pulling out my harmonica and giving it another try. But I didn’t. I wasn’t really feeling the romance of the road. I just wanted to get to Jackson Hole.

I wondered again why I did this. I thought about the yearning. I thought about the aimless angst of it all, the nameless desire for . . . something . . . and then about the sweetheart who was mine

no more. I thought about Dylan, and sang out loud “I’m just one too many mornings and a thousand . . . miles . . . behind.“

And I thought about Alienation. Alienation from what? I thought. Alienation from . . . God? From the universe? Alienation from myself? From. . . .

A car appeared down the road. It wouldn’t arrive for a couple of minutes, but I stuck my thumb out anyway. Alienation from what? I asked again, and stuck my thumb out towards the road

THE DAY I SAVED SEATTLE

James Knisely

(First appeared in HistoryLink.org, the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History)

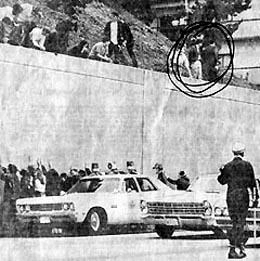

(Photo Seattle Times)

May 6, 1970: a birdsong balmy, lovely afternoon; the day I saved Seattle.

The tragedy that was Viet Nam was in its deepest throes, but the power of the flower was showing us the way that makes for peace. Even so, the way was steep and beset with dangers. Two days earlier, four college students had been slaughtered by a handful of college-age Guardsmen on the usually quiet campus of a university in Ohio, and the national mood had grown jumpy. I was still stunned and still wondering what was becoming of us: first the mayhem of riots in Watts and Chicago, and now the madness at Kent State.

I had just been married two months before and had found my first job a few weeks later, with the welfare department – not a great job, perhaps, but I was a man now, with responsibilities. Yet I had not given up my youthful hope of doing some good in the world.

Wednesday afternoon about four-thirty. I was on I-5 heading home; in those days you could still drive through Seattle on I-5.

But not that day. As I approached Downtown, I found traffic being shunted off the freeway. A demonstration the day before had taken over the freeway, and the radio had said another rally planned for today might do the same. Now, sure enough, a roadblock squeezed the interstate like a clamp.

My heart leapt. All day I had chafed at missing Tuesday’s march (bloody responsibilities!). I yearned to join the students and put my body on the line to stop the madman Nixon.

Or at least watch.

I drove up Lakeview to a grassy slope above those bulkheads that keep Capitol Hill from sliding onto the freeway. Tuesday’s children had marched peacefully from the University District into the city; now Wednesday’s were said to be coming the other way.

Others gathered on the steep hillside as word spread of the demonstrators’ approach. Most of us stood scattered across the slope, waiting, but a few leaned over the bulkhead and craned their necks to look down the vacant interstate into town.

I found a spot next to a woman wearing a batik dress and sandals, with white hair braided to her waist. She was old enough to be my grandmother.

“The killing has to stop,” she said to me. “I mean in Asia and here and everywhere. If they need someone to kill, they can just kill me.”

“Oh, I hope not,” I said. I loved this woman instantly, a beautiful woman, a saint. But I made a mental note to drift away from her if trouble started.

While we waited, two busloads of Seattle’s Finest arrived and parked along the shoulder below the bulkhead. Below us. The air across that hillside was suddenly charged with enough juice to power a Beverly Hills discotheque, and I began to sense that I might yet have some part in the unfolding of destiny.

Little did I know.

The officers were decked in riot gear, which had to be expected, of course: they were there to prevent a riot. Except that several of the officers were hanging out of the windows, beating the sides of their busses with yard-long clubs and whooping like born-again berserkers.

I began to wonder if I should have stopped. As the officers disembarked with their clubs and helmets and gas masks, it occurred to me that a certain innocence had been lost at Kent State—and that maybe I should have gotten the hint. The white-haired woman moved away and down the hill a little for a better look.

Below me on the hillside a scraggly kid of nineteen or twenty bent over and began picking up rocks off the ground. He dropped a handful into the pocket of his fatigue jacket, then bent over to pick up some more. Armed shocktroops were falling into formation below us, clamoring and lusting for blood, and this mastermind was getting ready to throw stones.

Before I could stop him, he pegged one of his rocks at the cops. My breath caught on something in my throat, and my life—such as it was—flashed before me. I thought of my wife. I thought of my job. I thought of the blood spilled in Ohio.

The rock fell short. In a brain-searing panic, I struggled to grasp what was unfolding before me. Watts and Newark and Detroit had burned and hundreds had died when the rock-throwing crazies and the bloodlusting cops had collided. Chicago had erupted into a riot fueled by the police, and now some of the Cossacks disgorging from these busses seemed to have exactly that in mind.

The kid was fishing in his pocket for more stones, so I knew I had only a split second in which to change the course of history—and he was out of reach, so I knew I had only words with which to reach him. I pictured Seattle in flames around my bullet-riddled corpse, my darling wife kneeling over me in grief like that famous young woman in Ohio.

I reached down, as they say, and found the words I needed, words both wise and hip, both streetsmart and profound, and with all the conviction of my heart I hurled them down the hill at the scraggly youth:

“DON’T THROW ROCKS!”

For a moment the earth stood still. Physical reality suspended itself in time as will and destiny faced off in Seattle. Then began a slow waltz in which every dancer emerged from a blinding haze into a pure and lucid clarity. A cop turned slowly our way; for a moment I thought I could see the blood in his eye. The woman with the long white hair began to move, almost floating, down the hill. Dancers young and old waltzed with dreamlike grace on the lawn of that Wednesday evening hillside.

And at last the kid turned around.

His face was a misery of confusion. He looked past me up the hill, as if the voice had come from somewhere Up There, from Above. The kid was plainly wired, though certainly not from anything that expands the mind. A look of abject stupidity washed his features while now he struggled to understand.

“Don’t throw rocks?” he said, still looking up the hill. He agonized a few moments more, a few lifetimes, perhaps, trying to discover the source of The Voice, then dropped his rocks.

And I began to breathe again.

The Cossacks stopped the marchers just below us and racked them against the wall. They got to crack a few heads and even launch a little gas, but they didn’t get to fire a shot. The forces of justice had moved and the forces of order had responded – but no one had thrown any more rocks.

A photograph of the scene appeared the next day on page three of the Times. It showed the police, the students. . . and me. I still have the photo. The cops have sixteen or eighteen of the demonstrators up against the bulkhead. I’m standing at the top of the wall, hands in my pockets, not looking at the arrests below me but off to my left in the direction from which apparently protesters were still coming. You can almost see me breathing again. You can’t see the scraggly kid.

My boss spotted me in the photo and circled me in black ink, then clipped the photo and left it on my desk. I’m not sure he bought my explanation about saving the city; all the same, he let me keep my job.

But imagine if that kid had hit some cops. Think of the headlines: “Protest turns violent in Seattle.” “Hundreds die in Washington State.” “Northwest city burns.” My life flashes before me when I think of it, even now.

I still wonder from time-to-time about the scraggly kid. I wonder if he made it through those terrible, exciting times, and all the terrible times since. That poor, dumb kid. I wonder if he knows he damn near got us killed. Or that the short guy behind him saved Seattle.

EYE CONTACT

James Knisely

(First appeared in Hippocampus Magazine September 1, 2015)

You see these people everywhere, anywhere you may have to stop or slow down: the freeway entrance, the freeway exit, the on-ramp here, the off-ramp there. Everywhere. They’re homeless, I suppose. That’s what their signs say: “Homeless,” “4 kids,” “Disabled,” “God Bless.” I suppose in some cases they really are, but how do I know? How am I supposed to know something like that?

I’ve made a New Year’s resolution to do something about it. Every time I pass one of these people, I’m going to put five dollars in a jar at home. At the end of the year, I’ll give the money to somebody who’ll know how to help. The Foodbank, maybe, the Homeless Shelter, the Mission.

But what counts as “passing” someone? What if they’re on the other side of the street? Or they’re on the exit side as I’m going in? Does that count? Do I owe five dollars then?

Maybe it should be about eye contact: every time I make eye contact with someone asking for help, I owe the five dollars. But how do I know whether they’re asking for help or just waiting for a ride? Okay, it’s if they have a sign.

Every time I make eye contact with someone who has a sign. But what if I don’t make eye contact? What if I have to turn away to look for traffic? Does that get me off the hook? Maybe I only look away because I’m embarrassed to make contact with these people. Or I think that if we do make contact, they’ll zero in on me and try to wring some money out of me that way. Does it matter why I don’t make contact? Can I still keep the five dollars? That would save me some money, all right … but I have to admit it defeats the purpose. So maybe it’s every time I make eye contact or should have made eye contact but looked away.

Unhappily, that gets us into the question of “shoulds”: “I shoulda this, I shoulda that.” We let our lives be crushed under the weight of shoulds and shouldn’ts. So maybe “should” isn’t the way to put it. Maybe it’s every time I could make eye contact but don’t.

But if I don’t make contact, who decides whether I could have or not? I can’t think of an answer for that one. If I spot a beggar across the street watching traffic from the other direction, is that a good faith miss? Could I have made eye contact? Who’s to say I couldn’t? Do I owe five dollars for every beggar I ever see?

Or I’m right next to the beggar but they just don’t happen to look at me. Hey, I can’t make eye contact with someone who isn’t looking. And what if I’m not sure? What if they seem to glance my way but I can’t tell whether they’ve spotted me or are just looking around?

Maybe it’s whether I make eye contact or would have made eye contact if I hadn’t looked away. I think that’s it. That way there’s no should or could, it’s just the plain fact of the situation—I’ve made eye contact or would have if I hadn’t turned my head.

I think that’ll work. That way I’ll know I’m doing my part without getting ripped off. It’s a good plan, and I’m feeling better about the whole thing.

I wonder if five dollars is too much.

TO DANCE WITH THE BEAST

James Knisely

(First appeared in Point No Point No. 8 Spring/Summer 1998)

THE WILDWOMAN & RELATIONSHIPS

A women’s workshop using stories from the book Women Who Run With the Wolves to explore the nature of deep love. Wear loose clothing, bring writing materials & a comfy cushion. Saturday 1-4pm. Freewill Offering. Please call Melinda Tilton Drexler, therapist 555-7387.

Ralph found this ad in the weekly newspaper he got. He loved it.

He decided to take out an ad of his own. He was a little surprised when the paper accepted it, but fifty bucks is fifty bucks. That seemed a little spendy, but he thought it would be worth it. “Life is short,” he thought. “Be bad.”

This is what it said:

THE WILD GAL & HER LOVES

A satisfying workshop using psychomythic legends from the book Gals Who Have Danced With the Beast to explore the satisfactions of deep, deep love. Bring loose shoes, a notebook of women’s poetry, and a soft doughnut cushion.

Phone 555-7055. Ask for Nadine.

The phone number was Ralph’s. He was beside himself the day the ad appeared—he could hardly wait to see who would be dumb enough to answer such an ad.

About midmorning the phone rang.

“Hello,” Ralph said.

“May I speak to Nadine,” the caller said. It was a woman, of course, with a very sexy voice, the voice of a neurotic, Ralph thought, the voice of a cigarette smoker.

“This is,” he said. He could hardly keep from laughing into the woman’s ear.

The caller hesitated a moment. Ralph’s voice was not the voice of a woman. Here is was Ralph’s voice was: breathy. It was a voice you would ordinarily think of as a man’s voice, but it had a quality that might make you wonder—not a woman’s voice, yet maybe a low, husky woman’s voice. Maybe.

“I’m calling about the workshop,” the woman said.

“Which one?” Ralph said.

“The one about the Wild Gal,” she said.

“I’m sorry,” Ralph said. “I’m not doing the workshops any more.”

“Not doing them?”

“No. I’m sorry. They were too wild.”

“Damn it,” the woman said, “I thought . . . Oh, never mind.”

She hung up.

Ralph roared the moment the woman was off the line. This was the best gag he had pulled since college. Almost as soon as he had hung up, the phone rang again.

“Hello?” Ralph said.

“Yes,” the woman said, “May I speak with Nadine?”

This woman sounded older than the other, and less interesting. Less neurotic, he thought, less sexy. Not a smoker.

“I’m Nadine,” he said.

The woman didn’t miss a beat.

“I’m calling about the workshop,” she said.

“Yes?”

“How long do they run?”

“Pretty long, depending on whether you get a long one or not.”

“Would you say all day? Half a day?”

“Oh, all day, when we do the all day workshop.”

“That will be great,” she said. “When is your next all day one?”

“We don’t have those any more,” he said.

“I’m sorry?”

“We don’t have the all day workshops any more.”

“Well, then, what do you have?”

“We’re not doing the workshops any more. They got to be too crazy.”

“You mean the all day ones, or any of them?”

Ralph’s diaphragm was trying to convulse. It took him all his strengths and energies to stifle the enormous laugh that was struggling to erupt.

“We don’t do any of them any more. They went insane.”

She was unflappable. “Well, good heavens,” she said. “Tell me about them, anyway. What were they actually about?”

“Why, they were about the Wild Gal. That sort of thing.”

“I’m just so fascinated by her,” the woman said. “Tell me about her.”

“Have you read Gals Who Have Danced With the Beast?”

“No, no. That’s what caught my interest. Where can I find it?”

“Oh, any bookstore. Just ask. I’m sure they’ll have it.”

“Thank you, Dear,” she said. “I’ll keep your number and call you after I’ve read it.”

They rang off. Ralph got a good laugh about sending this woman to a bookstore to ask for Gals Who Have Danced With The Beast. Probably to several bookstores—she seemed like someone who would keep trying bookstores until she found the thing. Somehow, though, he didn’t get quite the kick he had gotten from the first caller.

The phone didn’t ring again for almost an hour. Ralph had time to make himself another latte and read the newspaper.

His apartment was strangely quiet. The old mantel clock ticked and tocked and ticked and tocked. Ralph noticed that his apartment needed a good dusting; enough dust had collected on the window sills to throw little dust shadows. Ralph wondered if the shadows would move as the day progressed.

The old mantel clock ticked and tocked and ticked and tocked. Ralph decided to go out.

Then the phone rang.

“Hello,” Ralph said.

This caller was a man. “Hello,” he said. “Nadine.”

“Yes, this is Nadine,” Ralph said.

“I’m calling about your workshop,” the man said.

“Workshop?” Ralph said.

“Yes,” the man said, “your workshop. The Wild Gal and Her Loves,” he said.

Ralph sensed that the gag was wearing thin. “We don’t have the workshop any more.”

“Sure you do,” the man said.

“No. Actually, last week was our last workshop. I don’t know how that ad got into the paper.”

“Tell you what,” the man said. “I’ll hire you to do a private workshop. The Wild Gal and Her Loves. This afternoon. What do you say?”

“Well, we only used to do them in groups. It’s a group session, really. Exploration of the psychomythic thing really only works in the group setting. And we only did them on Saturdays. But I’m sorry, we’re not doing them at all now.”

“Of course you are,” the man said. “I’ll be over in a few minutes. We can explore the psychomythic thing then. I’ll make it worth your while. I promise.”

Ralph didn’t think he liked this. “No, that’s okay,” he said. “But thanks for calling.”

Ralph was about to hang up, but the man said, “I’ll be right over.”

“For God’s sake,” Ralph said, “you don’t even know where I live. Give it up, pal. Good bye.”

“Sure I do,” the man said.

“You do what?”

“I know where you live.”

“Now, how in the hell would you know that?”

“I got it from the phone company.”

“What do you mean, the phone company? They don’t give out addresses.”

“Then where’d I get it?” the man said.

“Bull roar, pal, I don’t really care. But thanks for the excitement. If we ever do another workshop, I’ll give you a call.”

The man told Ralph his address. He even knew the apartment number. Ralph could feel his face and his neck and his hands and feet begin to freeze.

“I’ll be there in a couple minutes,” the man said.

“I won’t be here,” Ralph said. “I’m going out.”

“Don’t,” the man said. “We’re going to dance with the Beast.”

Ralph hung up. He touched his face. Funny, he thought, how something so cold could sweat so hard.

His apartment was strangely quiet. The old mantel clock ticked and tocked and ticked and tocked:

Time to dance with the Beast, it said.

Tick-tock tick-tock:

Time to dance with the Beast.

FIRE

James Knisely

(First appeared in Knock No. 15, Feb. 2012)

Mary Jane runs into the burning house to save her Rothko and her kids. She is not hurt by the flames but wonders with annoyance why her husband sits so calmly in his corner reading yesterday’s Times.